Introspection

This page, and the resulting indulgence, is my attempt to organise and catalogue the most impactful moments of my development as a designer. It is neither chronological, nor complete. The chapters below amount to significant chunks of my journey from there to here; why I think and work the way that I do. I am painfully aware of how pretentious this exercise is - and the rest of the website too, really - but I’m driven by sharing, so here goes.

Chichu Art Museum Study

My fever dream in Naoshima, Japan.

I have long been obsessed with Japanese architecture, furniture, food, craft and culture. A dream of mine (and of my wife) was to visit the heralded Naoshima Island. A seemingly impossible place where my favourite architect, artist and culture teamed up to build my ultimate fantasy - a beautiful island off the coast of Japan, with a museum designed by Tadao Ando, featuring the work of James Turrell. Colour me agog!

Rising before dawn, we took the Shinkansen from Osaka to Okayama, some more small trains, and then the ferry to Naoshima, a 3.5 hour commute. Much to our surprise, we learned on arrival that while we were on the “closer” side of the island, we were still more than 2km downhill from Chichu Art Museum, and we’d already missed that morning’s bus. Like something out of The Amazing Race, we saw the other tourists - clearly in the know - power walking towards some small shops opposite the Ferry Terminal. We followed and saw that all three businesses were for bicycle rental. We got in line, and in shamefully bad Japanese, rented two bikes. In the scorching sun and sticky humidity of summer, we made our way to Chichu. We arrived to a sea of tourists and joined the back of the line to purchase entry tickets. When we finally reached the front, our tickets were for one of the last sessions of the day - we’d made it. (FYI, you can pre-book tickets online these days - this is a must).

When it was our turn to go through, it felt like we were the next in line for a roller coaster at Disney World. Tensions reached fever pitch as we were shuffled into a dark, cool concrete room. We received instructions and left big bags and items in the lockers. When our group of 10 was ready, the guide opened the door and ushered us into a shockingly quiet passage. It was almost completely dark, except for the light coming from an opening near the end. When we reached that light, we arrived at a beautiful walled garden in the shape of a perfect square, with ramp inside spiralling up to the the next concrete room beyond the courtyard.

This procession of compression and release, dark and light, concrete and sky, repeated as we meandered through the portals and chambers of shaped light and pure geometries. The ramps, slanted walls, narrowing paths and forced perspectives gave a dynamic, song-like quality to our journey as we shimmied from space to space gawking. This was the first artwork, Tadao Ando’s rhythm and architectural poetry. Some visitors may not have known that they were already experiencing the first artwork, but they would have felt the undeniable tempo and cadence in our wandering.

Next came a pinwheel of three choices that I now label: Time, with Walter De Maria, Nature with Claude Monet, and Space with James Turrell. Both fortunately, and unfortunately, we were not allowed any photographs in these artworks. Unfortunately, because I can’t show you here now, but fortunately, because these works need to be felt to be believed. Yes, seeing is believe, but feeling the phenomena of time, nature, and space is infinitely more impactful.

This project confirmed so much for me that I had only known academically. To know it intimately like this though, through touch, taste, smell, sound and sight certifies an undeniable truth; that what we talk about in books and lectures is genuinely possible, and that people, architects or not, can be moved in such a way that permanently marks their soul.

My Architectural Mixtape

Reflecting on my Naoshima pilgrimage years later, I see that, once again, the experience of a seminal work of architecture has etched itself into my way of seeing, thinking and making. Years of studying, experiencing, learning, absorbing, watching, recording, reading, listening, drawing, modelling, competing…all add to the way I approach architecture. And yet, this one building, in this single diagram, captures almost all of my architectural dogma.

I see so much of my Spatial History:

Kahn’s carving with light and starting with the rooms. Zumthor’s seductive light paths. Wright’s compression and release. Space-time with James Turrell. The role natural beauty plays in my (Bourke’s & Kant’s) understanding of the Sublime with Monet. Architecture as a witness - and a recording device - for time, with Walter De Maria. Holl’s light shafts. The Themenos and the walled garden. The black portals of my time at Pendal and Neille. Heidegger’s Hut. Bachelard’s poetics. Exploring pure geometry. Pallasmaa’s essays on phenomenology. Brutalism, Deconstructivism, and Critical Regionalism. And, of course, something my students tell me I never shut up about, Japanese Modernism - with Tadao Ando.

I didn’t design anything here, I just labelled things, but if were to make an architectural mixtape about my approach, my designer dogma, this would be it.

Spatial History

Leon Van Schaik’s Spatial Intelligence teaches us that we view the present through a lens made from every experience we have had up to this point. Equally, all architecture is viewed through the lens of every building, artwork, installation and so on we have experienced before - our spatial history.

We are constantly labelling new architecture as good, bad, boring, exciting, poetic, loud, thoughtful, careless, tasteful, horrific and much more. It is our spatial history that is filtering our experience and colouring our feelings one way or another. This happens whether we are conscious of it or not. Ignore it, and we run the risk of letting others (even our own subconscious) make qualitative decisions for us. If instead we reflect on our spatial history and pinpoint what we loved and what we hated, what sculpted us as designers and thinkers, then we can question and answer why we like something.

Our spatial history also becomes a resource to connect with and check against our own work. It might help us to make design decisions, to rationalise why we’ve made that choice, and to see if (our how much) we’re borrowing from others. Without spatial history, we design blind. Thinking the work is good, without knowing why, and hoping we’re on to something new, without actually critiquing ourselves in earnest.

The work below is an attempt to reflect on my own spatial history. I am fascinated by astonishing experience. In the simplest terms, this is classified by the moment my inner monologue says “wow.” In architecture, this is the when the space resonates with me in a powerful way. The light, the shadow, the material, the colour, the scale, the proportions, repetition of form, leading lines, perspective etc. are all working together in such a way that it pricks my attention and tingles my insides. It could be experienced in real life, or it could be an image or a film scene (see my Sensory Manifesto for more on this). Outside of architecture, it could be an phenomenal art installation, a rich artwork, a beautiful natural vista, or an ephemeral weather event.

Years ago, I spent months reflecting on what experiences astonished me and why. This culminated in two collections. Collection 1 is a series of quotes that resonated most with me, by the authors who most confirmed my spatial ethos surrounding astonishment. Collection 2 is a series of images that catalogues art, architecture, film, and nature that moved me in my past.

Collection 1

Quotes about astonishment.

Juhani Pallasmaa, Edmund Bourke, Immanuel Kant, Louis Kahn, Peter Zumthor, James Turrell, Le Corbusier, & Santiago Calatrava from various sources.

Collection 2

Experiences of art, architecture, film, and nature that have moved me personally.

The slides adjacent are either my own photos, or close representations from the internet/books that reflect the experience. Many of these experiences were first hand, others arose through films, journals, books, interviews, and perpetual sharing with friends and colleagues.

Astonishment in Architecture:

Interrogating the Ineffable, Sublime and the Cosmos through Immersive Technology.

Master of Architecture Thesis.

Abstract:

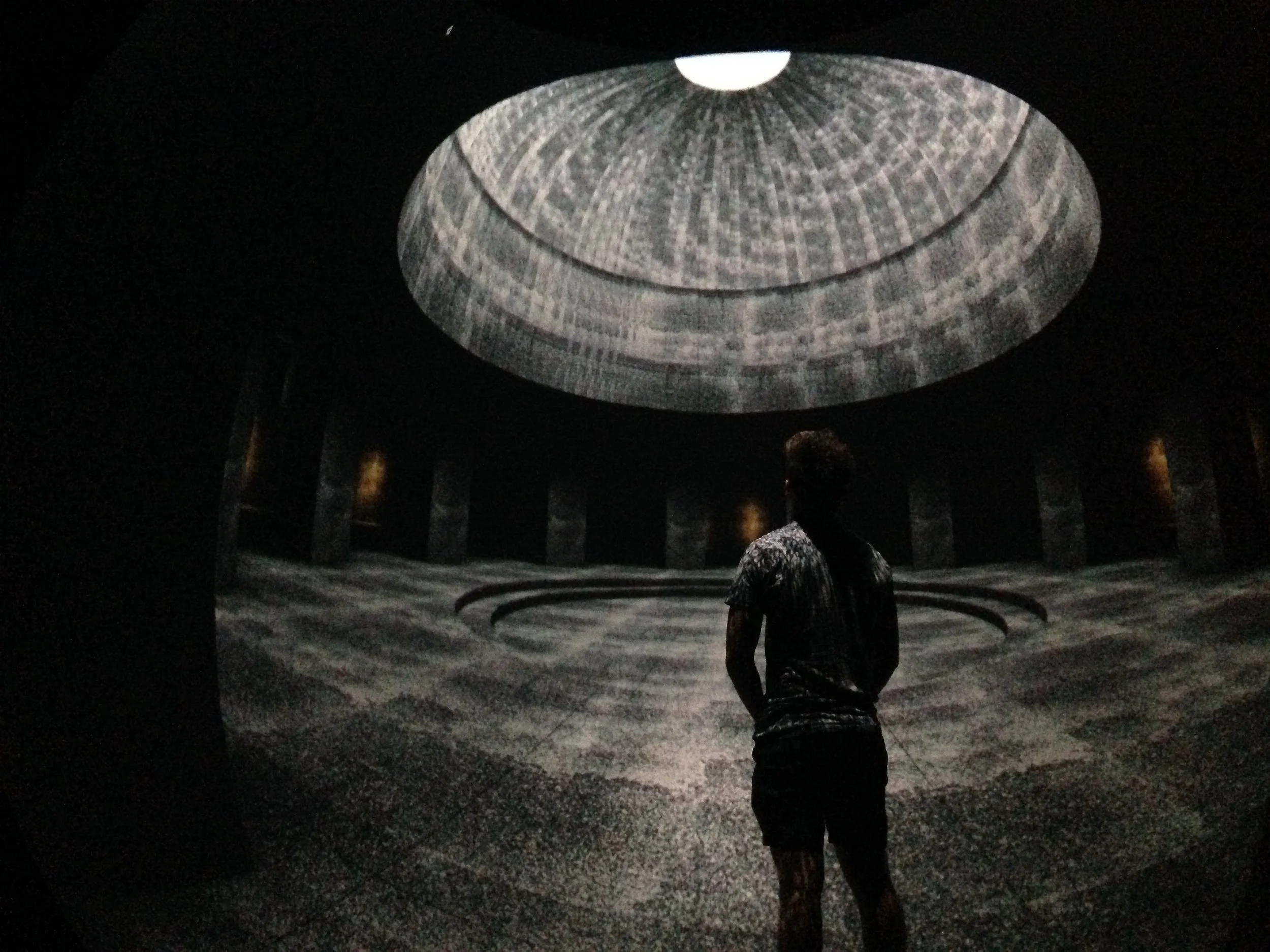

The height of human emotion, according to Edmund Burke’s “Philosophical Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful,” is astonishment, and is felt most often in the presence of natural phenomena (Boulton 2008, 57). The Pantheon in Rome, and James Turrell’s Aten Reign (2013) at the Guggenheim New York, are works of architecture whose deeply moving presence have marked my memory forever as places of absolute astonishment. This dissertation explores astonishment in architecture, seeking to better understand the field, and through the process of design research, create an approximation to it. The theoretical research undertaken proposes that astonishment in architecture is felt through the invoked sensation of great power beyond us and an air of the sacred. Through rigorous historical and philosophical research, the profanely sacred presence of extraordinary architecture, thought to underpin astonishment, is found to arise at the point of intersection between the philosophies of the ‘Ineffable’ and the ‘Sublime.’ Tangible parameters, such as ‘Light’ and ‘Obscurity’ are elicited from these philosophies and interrogated through the slow composition of a mixed use New York tower using immersive technology, including spherical projections, at Curtin University’s HIVE laboratory. Expanding on knowledge gained through an iterative process of building, experiencing and reflecting, the final design, namely three rooms of grand sacred presence, is crafted through a film that further investigates the elicited tangible parameters, and also approximates an extraordinary experience. The findings of this dissertation highlight the power of the elicited tangible parameters to create an architecture that is beyond the ordinary with a strong spiritual presence, and affirm the influence of a connection to the sacred in the path to grand experience. Astonishment in architecture was originally felt in real inhabitable spaces; therefore, immersive technologies and film are used for a more genuine experience than traditional drawing or modelling techniques. The outcomes of the dissertation are; new immersive methods of design including, spherical projection, a digital Manuscript App, and film interrogation; a deepened understanding of the power of sacred presence in architecture; and three wondrous rooms in a New York tower that approximate close to architectural astonishment.

Thesis Film.

Master of Architecture, 2014

(Yes, visualisation’s come a long way since! Please forgive the dated graphics).

This film is an exploratory investigation into the contributing factors to awe in architecture. Here we test the parameters of astonishment found at the intersection of the 16th Century philosophy of the Sublime, and 21st Century architectural theory (see full thesis above). Using the Curtin University's HIVE laboratory I explored said parameters by placing myself inside hundreds of 360 panoramic projections. This film attempts to communicate the development of three spaces in a tower. The flashing of spatial options is a filmic abstraction of my iterative process of investigating the tangible parameters of astonishment in architecture. Visualisations were made using free software available in 2014. The design itself is irrelevant - the process of “physically” interrogating the underpinning philosophy was the important outcome.

Within Without

A study of James Turrell’s phenomenological event.

This time lapse condenses about an hour - 30 minutes either side of dawn. As you might read below, this installation takes the viewer on a phenomenological and existential journey through space and time. James Turrell's Within Without is a permanent installation artwork at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. Twice a day, at dawn and dusk, magic happens. The Skyspace simply brings it to light...

For a close-ish approximation of the narrative below, try your best to focus your eye, unwaveringly on the oculus in the video.

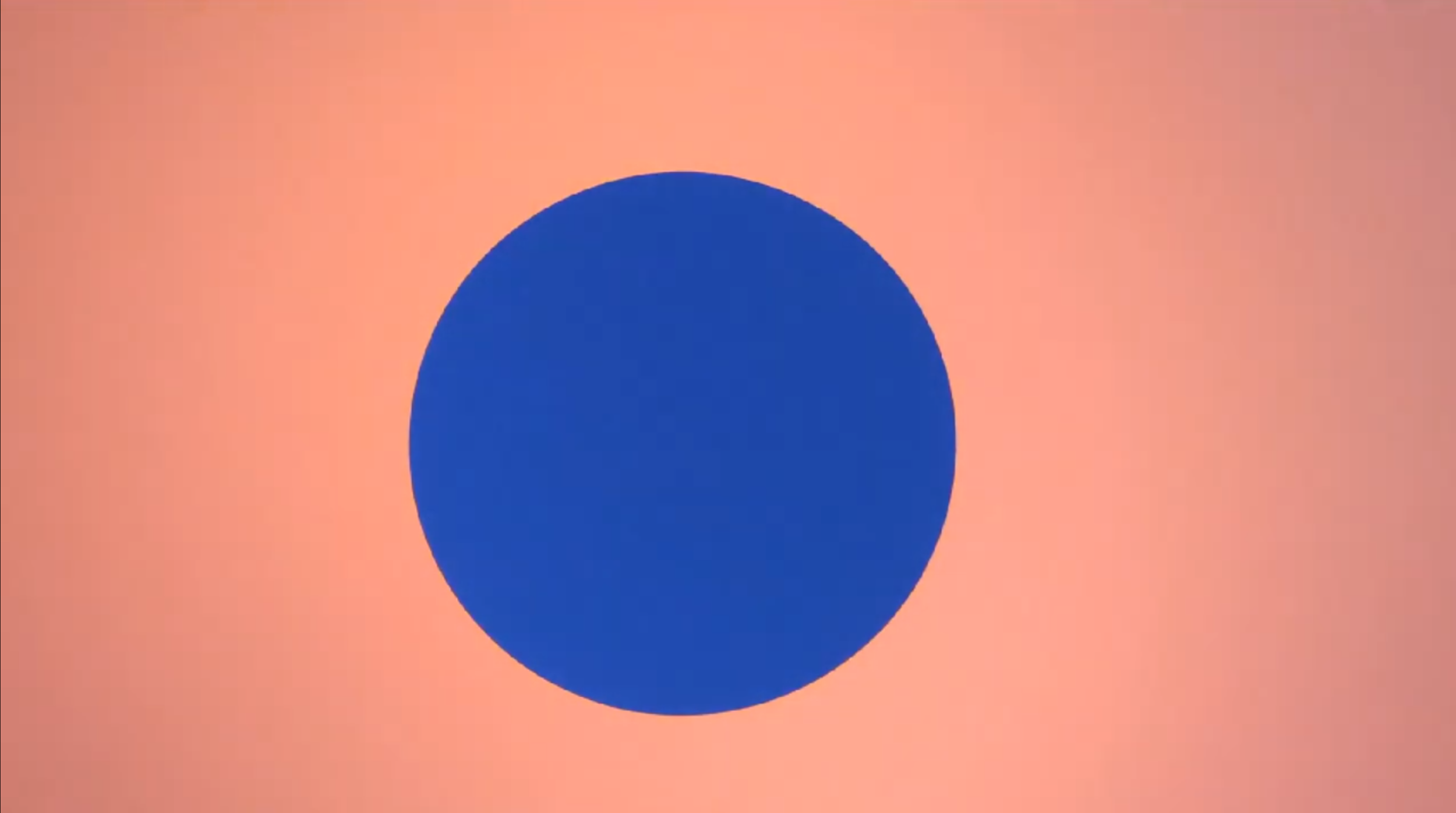

Angled (and thankfully, heated) seats direct your gaze to the paper thin oculus and the night sky beyond. In the freezing Canberra stillness, you stare through the oculus into pre-sunrise darkness. The domed ceiling is positioned and proportioned above you to fill your field of view. The cold LED lights paint the ceiling white, and comparatively render the oculus as an a black hole stretching infinitely beyond, like a cartoon eyeball staring back at you. Just as you get comfortable with the colossal eye, the dome's LEDs crash into an ocean of Prussian blue, and the show has begun.

You continue to stare at the oculus as the dark blue shifts to deep purple. The colour is changing so slowly and seamlessly that you have to convince yourself it was purple earlier as you only see pink before you. Pink shifts to blood-orange, and then back to purple, all the while you're ever-focused on that black dot. If you weren't sitting down, you might succumb to vertigo as things start to get weird. Your oh-so-trustworthy eyes seem to play tricks on you as the oculus begins to grow steadily and consume your vision. It turns out the great eye above was actually an open mouth the whole time. It's now a hungry mouth expanding through space in all directions, raining down upon you like a cosmic, toothless shark swallowing a tiny plankton through its open-mouth swim.

You pull focus again and shake the silly dawn-dreams from your mind. The oculus shrinks back to a black dot framed by an endless depth of colour. The next oddity follows soon after as a ring of light circles the oculus, the same colour as the dome, but somehow brighter and more intense. While you're smiling in disbelief, knowing full well that there are no lights around that oculus (you inspected everything when you first arrived), the oculus, the ring and the dome flatten themselves into an infinite plane just beyond your reach. As though a simple graphic on a poster, a black circle on a colour gradient, you feel as if you have entered a two-dimensional sub-world, and that stretching your hand out might puncture the plane before you.

As you gaze up in child-like wonder at the flat-earth illusion, you pull-focus again and notice the oculus is now the one being swallowed. The sky beyond is getting lighter as dawn approaches, and the colour spectrum of our dome briefly matches the shade of blue in the night's sky. For a fleeting moment, dome and circle become one in an infinite field of navy as we wonder if our friend the black dot will ever return. The hue glides slowly back to pink and we feel faint relief as our dot creeps back from the shadow - but as it does, we realise an imposter has taken dot's place. Now a shade of deep blue instead of infinite black, we must acclimatise to this stranger. In the dome, pinks shift to purples and then blues, and blue-dot disappears again, reigniting our hopes that black-dot will return.

As the dome's blues shift to oranges for the first time, blue-dot returns - and with quite the flourish! Cleary having returned from a transcendental journey, blue-dot emerges from its cocoon as a fantastic electric blue. Now, as we dance from orange to light-pink we enjoy watching our new friend radiate energetically.

In a final trick, our eyes deceive us once again as colours continue to morph. This time the oculus itself appears to be changing colour, from that electric blue, now to a vibrant green, and then to pink?! How can this be? We know that the dot is just the sky, and we know that the electric blue is the real colour, so what's going on?

As we try to rationalise this illusion we notice the dome is no longer coloured, it is now white and the mischievous oculus is back to our favourite blue. We enjoy this calm composition and continue watching on as the dome lights slowly fade away, leaving only the ambient light from the freshly risen sun, and the pale blue of a new morning sky.

Within

Between?

Without

What’s in between?

Back again. This time we look at Turrell’s Skyspace from the perspective of spatial thresholds. The installation’s title Within Without implies a binary position, that we are either inside the Skyspace, or outside it.

Architecture can be - and often is - considered binary too. If architecture is the perception and experience of space that is shaped by erected form, then we simply occupy the voids shaped by the solids. Solids are ones, voids are zeros.

A more alluring view of architecture is that it is not binary, and that there exists a spectrum of spaces for us to occupy. We can be completely inside the space, but we can also occupy the thresholds or in-between spaces; the interstitial plane. These are moments where we transcend from one space to another, yes, but they are also spaces themselves, and when expanded, can be occupied as stand-alone moments.

This study looks at the interstice of Turrell’s Within Without to find the realm between the two. Perhaps Between-Within-Without.

The image above was taken lying face up in the interstice capturing the oculus and dome to the left, the sky to the right, and the between space as the black threshold in the middle. This is the raw image. No photoshop, not colour correction.

The black arc - our between space - highlights the both the ambiguity and unknown of the threshold and also the intrinsic and intimate relationship it forms with both sides. It is equally connected to in and out. It is both inside and outside. It is a secondary zone, but a primary experience.

-

Within

Inside the space, we partake in the function and experience the void formed by the solids. We are fully immersed within the primary space.

-

Between

We occupy the interstice, the threshold between inside and outside. Frozen in time, we have not yet left outside, nor entered inside. We exist in the moment between. Later, when we intend to leave the primary space, the experience is inverted. We have neither exited inside nor entered outside. The threshold is unavoidable. Inside is impenetrable without it, as is outside. The threshold permits passage, but also inhabitation. When we linger in the threshold, we can enjoy occupying both realms.

-

Without

We are outside the space. We have either arrived at our destination, or have just departed. In this moment we are disconnected to within, we are without.

Seeing Space

Selected works

This series explores the role of the end-user in architecture. A vertical panorama records both the occupier of space and what that occupier see from their point of view. Architecture is always experienced from a first-person perspective. It is impossible for us to see what others see. As such, the experience of architecture is fundamentally intimate. Our experience of the space, is ours alone. Seeing space attempts to translate the first-person perspective of architecture into a shared moment of collective experience.

The planted feet of the user (mine in these cases) remind us that we the users play the lead role in the experience of architecture. Architecture is inherently democratic, the most public of all art forms. Regardless of the architect’s intent or hopes for their architecture, it is ultimately the user who will determine how they occupy the space. If we want to climb a balustrade we will, if we want to knock down a wall, so be it.

As per the laws of physics, only one user can occupy a specific point within architecture at any given time. However, the action of taking a body-portrait and a first-person perspective, allows us to de-privatise that particular moment and share it with anyone. The photograph is a collective memory. Now, anyone can inhabit this experience from my perspective.

-

Libeskind's Contemporary Jewish Museum

Daniel Liberskind is renowned for his take on deconstructivism. His collision geometric and angular forms create deep crevices and left over spaces inside and out. Here I squeeze myself into the depths of the crevice adjacent the now iconic entrance.

-

MoMA's Sculpture Garden

MoMA New York is a haven for Modern art and its many evangelists. On Fridays, the museum waives their fee so that everyone, from any walk of life, can experience the art for free. Sometimes they put on a free concert at lunch time too.

-

Belluschi & Nervi's Cathedral of Saint Mary

Bourke and Kant’s philosophers of the Sublime suggest that astonishment is the experience of something beyond our comprehension, that immensity and the unknown make us feel both insignificant and connected to a higher power. (See thesis).

Sensory Manifesto

Work in progress, incomplete.

Following from Collection 1 and Collection 2 of my spatial history, I have become increasingly fascinated by the capacity for architecture in film and game to move me. In most films, many scenes take place inside or outside architecture and built form, and that’s nothing new or special. There are, however, some architectural scenes in film that genuinely spark awe within me. The same happens (although less frequently) in games.

My question is why are some spatial scenes in film so powerful? In order to answer this, I started collecting the scenes that moved me the most across the years and figure out what they have in common. Rather than getting bogged down in the intangible nature of plot and characters, I identified the Tangible Parameters: the architectural, photographic, and filmic tools used in the scene that culminated in awe. Then I cross-referenced all of the scenes to figure out which parameters kept coming up for me, again and again. The more a Tangible Parameter came up, the more influence I could objectively say it had on the architecture’s impact.

The most impactful tangibles for me are… (work in progress).

This exercise became the assignment one project for my Third Year Architectural Methods students at Curtin University - see Teaching.